I've been missing in action. I apologize. Sometimes life intrudes.

Tonight I'm going to include some paintings from the archive, trying to keep you awake.

|

| Housatonic, 1988 |

Visiting Hours

This week I've had two visits from artists and a visit from my Boston dealer (Chris Quidley). Chris got to see three new paintings in process, all headed to Boston and then on to Nantucket. All three have been on the blog. The cows (40x48",101x121 cm), Recovery Room (36x60", 91x152 cm) and the Hayloft (36x28", 91x71 cm). They are each close to completion. I'll try to photograph them for you before they leave the studio.

|

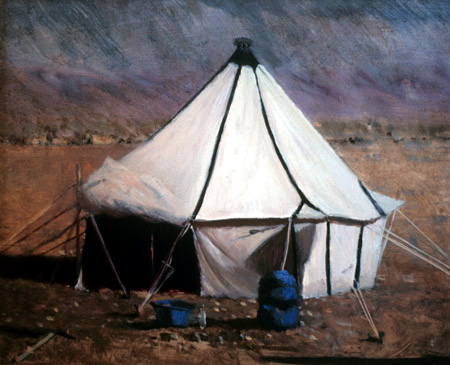

| Our Tent in the Atlas Mountains, 1990 |

A Large Painting to do for New York

Additionally, I've ordered stretcher bars for another large painting. It seems, through a miscommunication, that I will have a unexpected frame on my hands (78 x 48", 198x121 cm). My New York gallery (Arcadia) wants me to make a vertical in this large size. You can imagine how daunting that is! In any event, the bars are coming from Upper Canada Stretchers. I have never used them, so we'll see what comes. Several students swear by them. I'll let you know what I think.

|

| A Farm in France, 2008 |

|

| A Glimpse of the Hudson, 1982 |

Here are a couple of answers.

First, from K. W., an undergraduate at SCAD, who was a scholarship student at the recent workshop we held in Savannah.

I was just wondering what would be your top 3-5 tips for en plein air and/or landscape painting in general? I am taking a landscape painting class starting this quarter, and I wanted to refresh my mind on what you talked about.

Hmmmm....

1. Take the time, where practical, to walk all the way around your subject. Understanding what the back of your subject looks like will help you paint the visible side better.

2. Remember that every extra minute you spend in working out your composition, values, and general drawing---while seeming sometimes tedious at the moment----will yield great rewards when you start in with color. There's nothing worse than painting the best tree you've ever done only to find out it would be better placed if it were two inches to the left. Do yourself a favor and get it right in the beginning.

3. Paint with transparent colors as long as you can in the beginning of the painting, bulking up the forms, establishing values, etc. You can always add opacity to these where needed, but you can't get that shimmering translucency back once you've lost it.

4. Keep walking back from your painting, constantly. Don't paint sitting down if your constitution permits. Getting a few feet away can often show you what's working and what's not.

5. After an hour or so, take a hike for ten minutes. You'll come back to your painting with eyes that are refreshed, and you'll often be able to instantly see the solution to a problem that seemed overwhelmingly thorny ten minutes before.

|

| A Promise of Fair Weather, 2008 |

I wonder how you re-paint, re-prepare a canvas in order to

paint a new scene on the same canvas with grisaille? can you re-cover the

already painted canvas with white oil color, and then re-engage yourself with

turpentine for the grisailles? What about the fat on lean process?

Well, I'm no physical chemist, so I can't enter in to too much of a discussion about fat-over-lean. The best explanation I know, describing fat-over-lean, is the example of an inner tube. Paint a section of an inner tube with some white house paint. When it's dry, inflate the tube. You'll see what the issue is.

In my case, I paint so thinly that there aren't continuous, solid paint areas in my work. I don't expect any problems from fat-over-lean. But, if you paint with any sort of real thickness, it's an issue you want to be aware of.

Generally speaking, if I'm painting over a previously painted surface, I just do the grisaille without preparing the canvas. I can usually get enough of a drawing on the canvas to see where I am.

If your canvas is so dark that you need to lighten it to see anything, you ought to take another, different one. If, however, you're stubborn(!), you might try scumbling a veil of white over the canvas, allowing it to dry completely before you continue. But, as I said, I'm no physical chemist---so you didn't just read that.

Most of us rarely make a painting that will be in the Metropolitan Museum for centuries after our deaths. So, if it's just a painting for you alone, a chance to learn and to experiment, just go ahead. If, on the other hand, the painting is destined for the Tate, why not splurge on a new canvas?

|

| A Moroccan Market, 1990 |

A correspondent in France asks how I developed my particular way of establishing an underpainting in grisaille before I carry on to the color.

The painting above, about 12x20" (30x50 cm), is an example of how much you can get in a short time with just a grisaille. It has no color except a variable mixture of burnt umber and ultramarine.

My method came about because I didn't have much instruction. I knew what I wanted to do, but I found that keeping a lot of balls in the air at the same time (composition, values, drawing, color) was beyond me. So I sought to break down the process into manageable bits. By working in what is essentially monochrome, I could solve problems without being bewildered by the 10,543 color decisions that lay ahead. When I was confident about the drawing, the arrangement, and the value scheme, I could go ahead, as Winston Churchill described it, and take a joy-ride in a paintbox.

Now I can get into the color more quickly if I wish, but I almost always do a grisaille first.

One day on the Scotland Workshop last fall we had a deluge near the beginning of the painting day. Because I'd concentrated on a grisaille, and finished it, I was able to have a serviceable souvenir when others only had a few color notes.

One thing to remember: if you do a good grisaille of some spot, and take it home to dry, you can go back to the spot any time you like to make a painting. You'll be all set and, because you've already done an underpainting, you can more easily capture evanescent light effects.

Send me questions please, to my email at dbjurney@verizon.net or ask a question in the comments, below.

Happy Painting!

Donald

For other artists out there in your studios, Donald's painting reminders about the Grisaille method, is the key to a successful painting. Working with transparent colors allows us to build a painting slowly. There have been times, ( recently) had to wipe out a troubled canvas with too much paint on it. Not the way to begin. Because the Grisallie was there....wiping away the excess paint only cost me several hours work, and back again to remember, transparent paint!

ReplyDeleteKeep trying, takes time for all of this to become a habit. Thanks, Donald!

Great stuff! More, please! :)

ReplyDeletePS "Promise of Fair Weather" is very evocative...

ReplyDelete